puparia – the hardened last larval skin which encloses the pupa in some insects, especially in higher dipteria – a hard barrel-shaped case enclosing the pupae of the housefly and other dipterious insects.

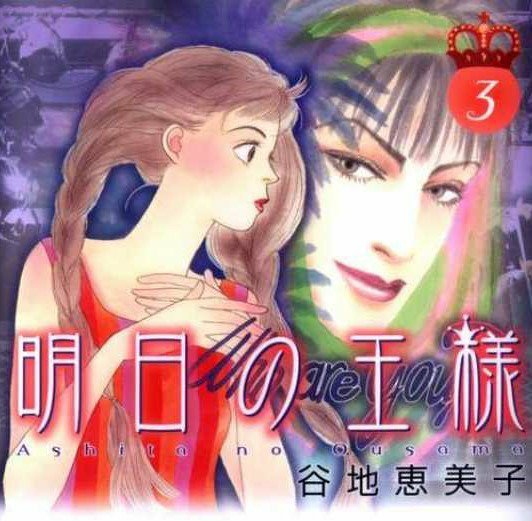

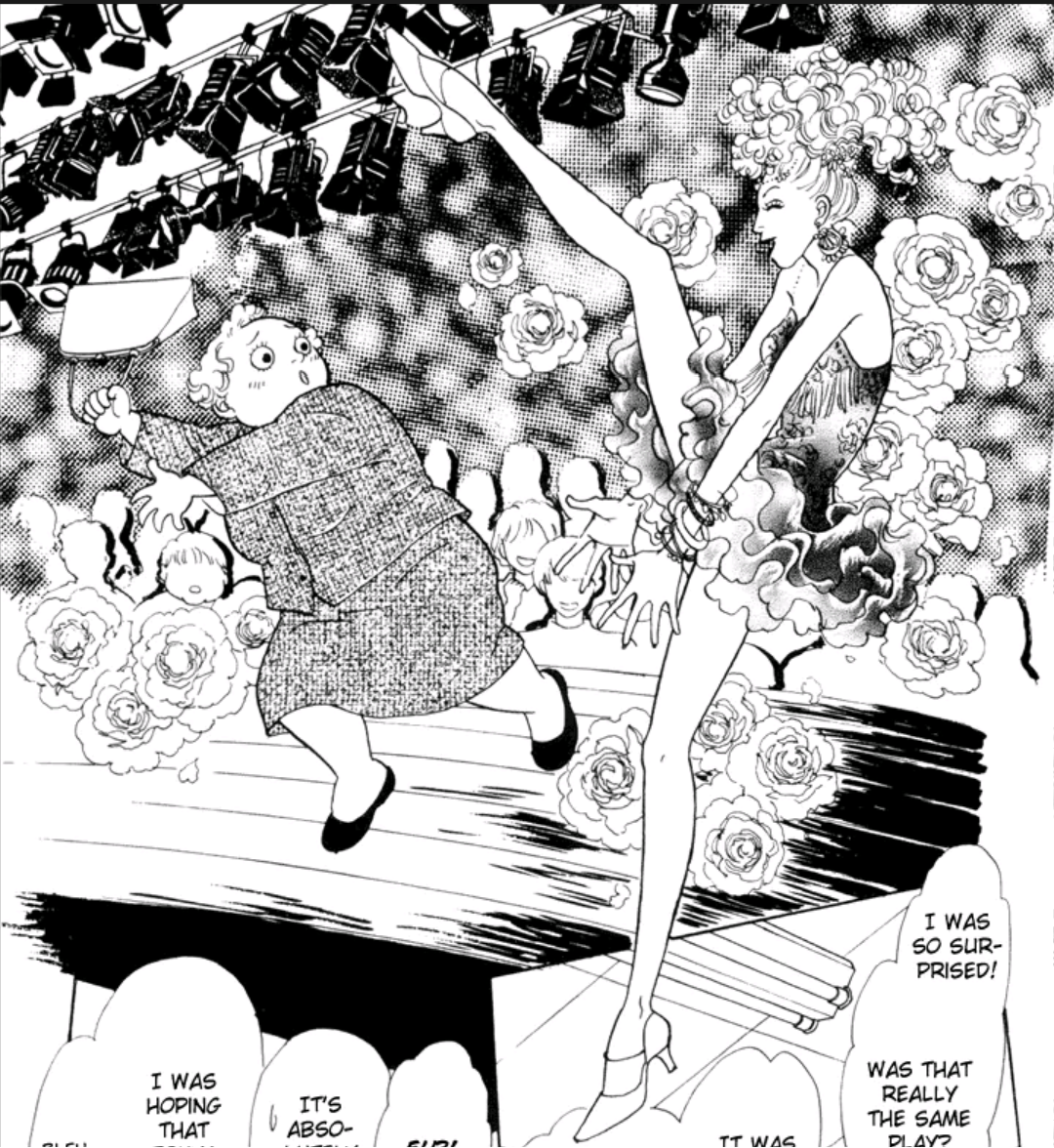

Now, speaking frankly – I have no real idea what any of the words above mean. But before searching up the word, I knew PUPARIA was the perfect title for Shingo Tamagawa’s short film. His first foray into indie animation is a lot of things – strange, seductive, alarming, confusing -but tying it all together is a fascination with the primal, the animal, the insect. In the film, the insect is the rawest, purest form of nature. The girls – or the unambiguously human figures – are put against a backdrop of natural imagery. Tamagawa’s art direction is striking as he contrasts their relatively simple designs against meticulous colour-pencil backgrounds. The use of colour-pencil itself, as opposed to paint or digital mediums, is meaningful – it adds to the rawness of images that assault the eyes. But the short is most fascinating when the different visual elements merge, when the lines between the human and the animal begin to blur.

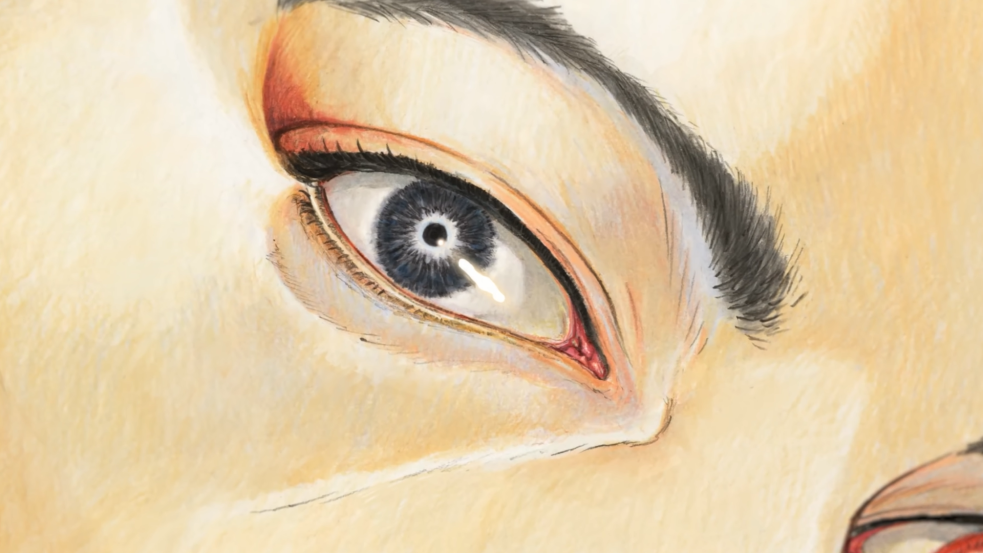

A seemingly infinite hallway, where a man – is he man? – stands at its door. From the darkness of the hall, a moth-like figure emerges. Whenever I watch this segment of the film, I’m always disturbed. The emphasis on eyes – the intense gazes of both non-human figures right at the camera- puts me on edge. I become strangely aware of watching in the same way these characters watch me. It’s a scene that both demands and repels understanding. The seemingly arbitrary details, like the man’s right eye, collide with the urgency of the creature that practically leaps out of the screen. What am I supposed to take from it? Is there even anything there, besides vague feelings of wrongness?

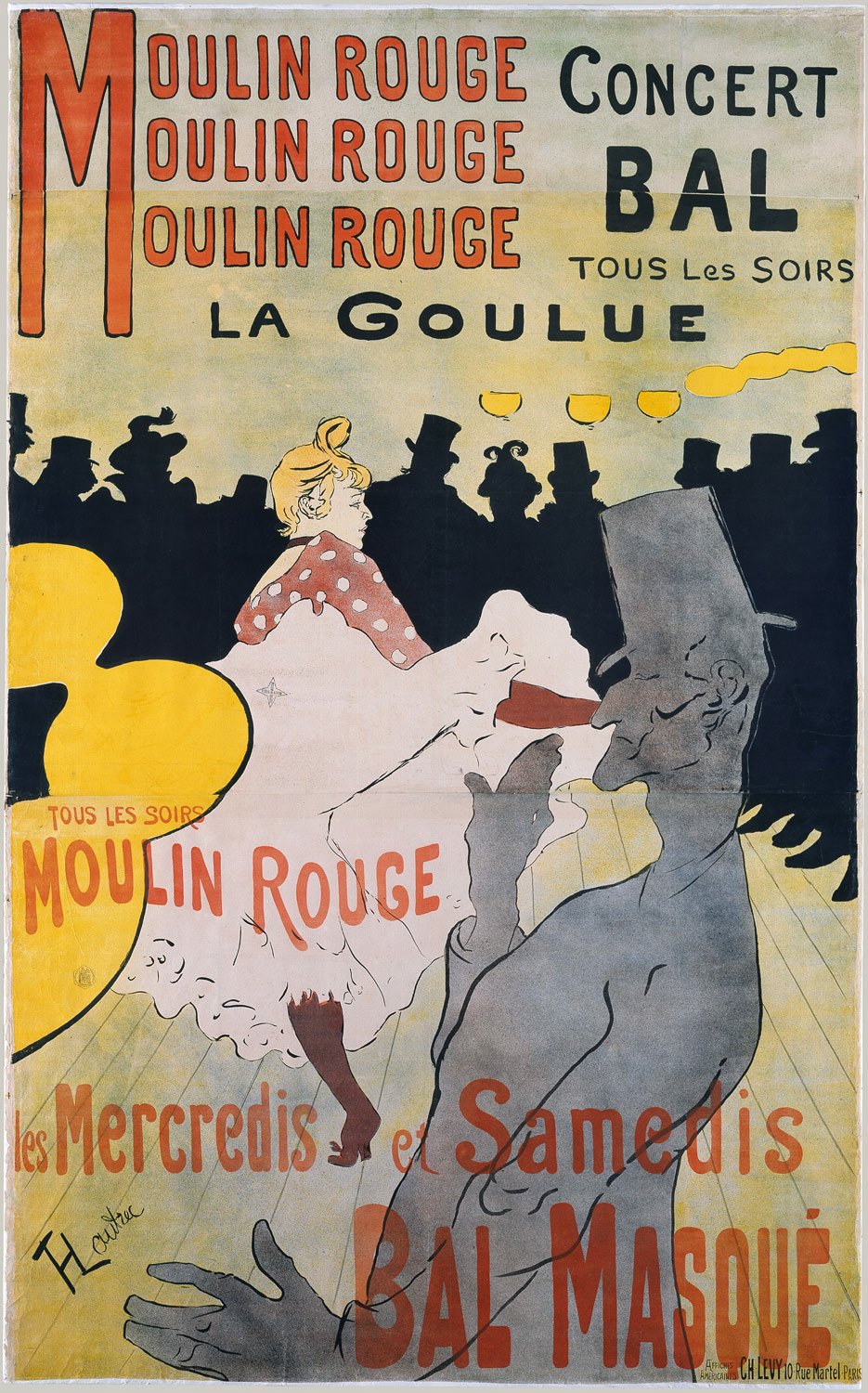

A film like PUPARIA challenges my ability to communicate meaning. What it means to me isn’t tangible – there’s no clear narrative to cling to and elucidate. It’s a deliberate piece of art that touches on subconscious images – images that we recognise on some subliminal level, but aren’t conscious of until it startles us with its sudden presence. Take the final scene – I don’t know if there’s symbolism and what that symbolism could mean. But I connect, on a fundamental level, with the images of the masses observing the alien figure. As Tamagawa draws out the individual faces from the collective, I’m drawn into that narrative itself. It reminds me of the times when I visit London. I step into the city, and lose myself in the crowds. But throughout the day, the crowds thin and disperse until I can recognise faces and find my place again – and it’s only when that happens that I feel like I’m truly part of the city. And being part of the city is being part of a complex web of nationalities, races, experiences that make London – being myself and not at the same time. It’s not a sensation I often think about, but it’s been drawn out of me by the simple image of a crowd – who might represent “civilization” – watching an alien other.

Talking about art can be (unnecessarily) convoluted. Since I started my degree (Comparative Literature, a degree that can’t even define itself), I’ve encountered the myriads of ways people find to communicate how they feel/interpret/connect with the art they love/hate. It’s been both enlightening and baffling. Every piece of criticism I’ve read has skirted this fine line between compelling critique and pretentious rambling. But watching PUPARIA, trying to sort out my feelings about this weird, random short, I’m starting to understand that in those contradictions is an earnest desire to unearth complex feelings about art, about society, about oneself and maybe, even about life. PUPARIA is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen. It’s a film that marries illustration and animation to convey an uncanny story about…something. I don’t know what that something is, and that’s the beauty of it.

I really should’ve written about this film earlier, but honestly, the last quarter of 2020 was a lot. I’m not very good at talking about real-world affairs on this blog, but these last five months have been bizarre. It’s telling that my only reaction to PUPARIA at the time was “huh, that’s cool”, before shoving it to the back of my mind to focus on finishing my first term of uni in COVID conditions. The Sakuga Blog’s 2020 recap reminded me of just how amazing this short is. It’s the sort of art that I aspire to create one day, and I’d love to see more of Tamagawa’s work in the future.