This post contains mild spoilers for Akiko Higashimura’s autobiographical manga, Kakukaku Shikajika. It really relies on your knowledge of the manga, so I recommend you check it out before reading this post, which honestly doesn’t do the manga any justice. It’s really good 🙂

I discovered Kakukaku Shikajika through Manben, a documentary series produced by Naoki Urasawa with the aim of providing insight into the working habits of professional mangaka. Before that, the world of manga-making had been mystical, hidden behind the lie of effortless, untrained talent. Manben brought the artists down to something close to human, and Akiko Higashimura was the first artist to be featured. I was hesitant; I wasn’t a fan of Higashimura’s style. But, for whatever reason, that episode stuck by me. Akiko Higashimura draws like a master, her pen flying across the page at record speed. It was fascinating to experience an artist’s performance without even being a fan of the end product. I think, I was struck by her ability to just draw.

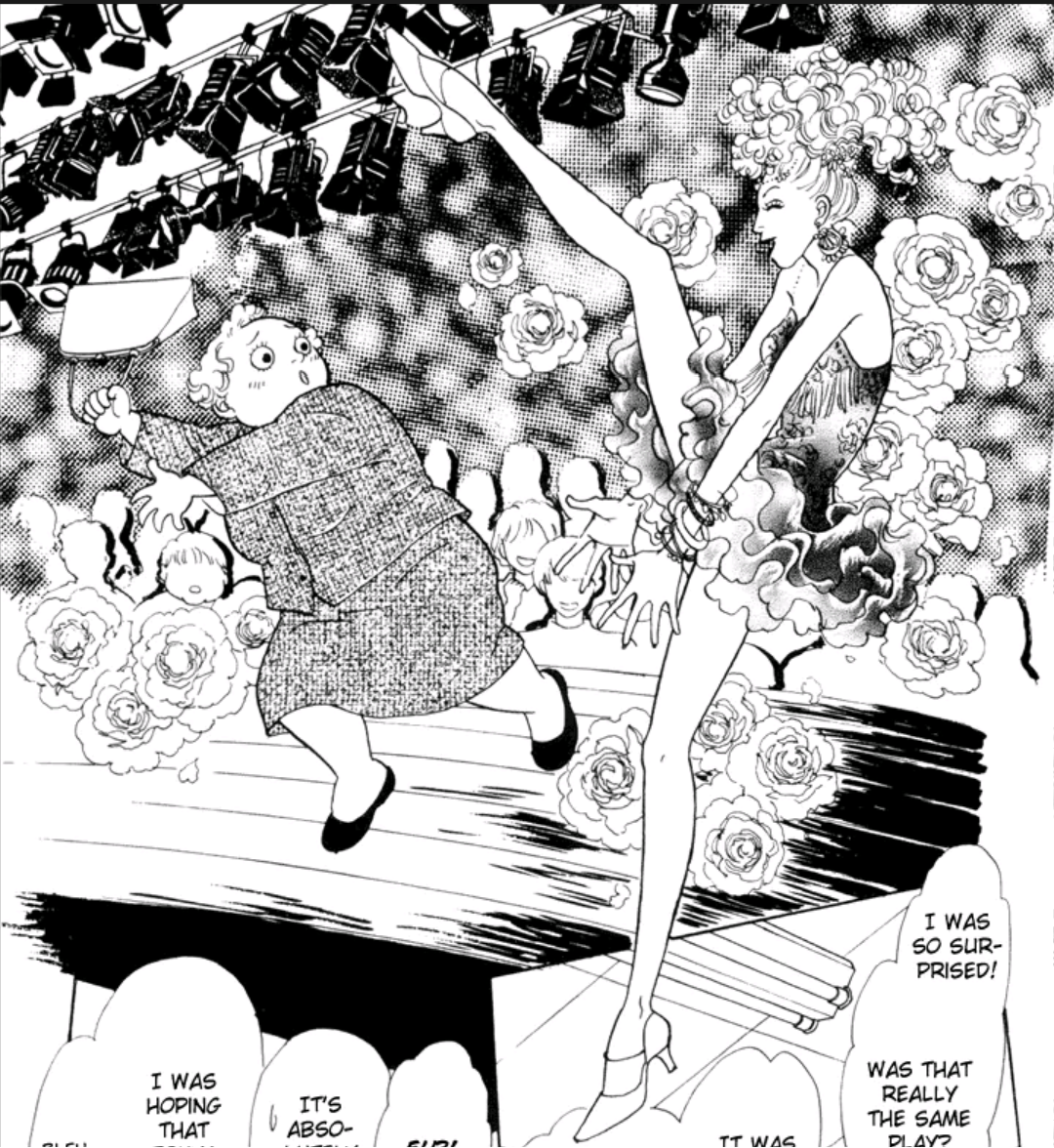

Drawing is the recurring theme of Kakukaku Shikajika. Obviously, since it is Higashimura’s autobiographical tale of how she got into manga, but the story takes drawing on a more personal, introspective level. I had never seen mangaka as being in love with art itself- I felt a strange emotional disconnect; the drawings were merely being printed out, secondary to the story. I know, it makes no sense! But that’s just the way it was. I carried that attitude into Kakukaku Shikajika and initially, it was no different. Akiko Higashimura paints her younger self as this grandiose, self-obsessed diva with an apocalyptic ego. Her head is so firmly in the clouds that it becomes clear her desire to become a mangaka isn’t one she treats with much weight.

That’s where Sensei comes in. Sensei: enigmatic, off-kilter, innocent, over-eager. His hardworking ethic and straightfaced, ridiculous seriousness form a sharp contrast to Akiko’s vapid uber-teenage behaviour, but it’s fun and funny. In those early chapters, Higashimura flexes her strengths in gag comedy to create nostalgic chaos, as we see Sensei bully his students into better art technique. However, it becomes clear that Sensei, for all his harsh words and acidic temperament, is in love with art. It’s a pure, childish love, the love of someone with complete faith. It’s total self-discipline. Akiko goes along with his regiment, but without true understanding of the gift he’s bestowing on her. She’s too young, pig-headed and naive. Years later, she will look back and think, “Ah, why didn’t I realise sooner?”

University happens. It’s Akiko’s dream, to study in an art university and debut her manga whilst in uni. There’s supplies, studios, beautiful models to be painted, professional tutors to mark your work, the atmosphere of being with other talented, driven art students. It’s perfect. It’s the breeding ground for growth and Akiko is ready. Or is she? The irony is that under stress, surrounded by schoolwork, being beaten by a crotchety art teacher, Akiko draws fine. But with all the resources in the world, Akiko just can’t draw. She thinking too much about it, being too impatient. She’s stuck.

There’s something Higashimura says as she looks back at this period of her life:

“Drawing means being covered in charcoal, reeking of paint, intently moving your hand, thing not going your way, struggling over the paper, and while continuing to struggle, whether unexpectedly or inevitable, every once in a while, there’s a moment when you find merely a single stroke you find satisfying. Bit by bit, you take that stroke and connect and build upon it, and just simply repeat it.”

Before you find that stroke, art is agonizing. You’re on edge, the marks you put on paper don’t make sense, and everything looks ugly. Staying patient in that period takes serious self-discipline, and when you’re stressed, depressed, nervous, tired, it’s hard to take a painting past that stage. Things have to look ugly before they can be beautiful. It’s nature, but it’s hard to remember when you’re trying out a new medium and you’re painfully aware of every stroke you make across the page.

So we watch as she slowly abandons painting for play, for good times. Her palette dries up and her brushes turn hard. And we watch her watch herself becoming apathetic to the medium, as art block and laziness turns her love for art sour. She forgets Sensei. The desire is still there (and the guilt, like a lump in her stomach) but she can’t help it. For the first time, Akiko can’t draw. She’s thinking too much, and thinking too little. I’ve been there, I thought, whilst reading this manga. I’ve been there and it hurts. I remembered my love for art, and I missed my love for art, but I wasn’t chasing it. I wasn’t running after it, clamouring it back. That hurt the most- that I had stopped chasing after something that I had loved so much. I had stopped caring.

For me that period lasted a handful of months, but for Akiko it lasts the four years she’s at university. She produces nothing of worth, wasting her parents’ hard earned cash to mess about with a bunch of similarly demotivated, slacker classmates. At the end of 4 years, she has nothing to show for it but unemployment, as Japan moves into the worst phases of its recession. She returns home a ‘vagrant’ and is forced to take up work in her father’s company to make up rent and food. In the meanwhile, Sensei employs her as a teacher to new students in his art group, who are now in her position of working towards art school. There’s a lot of emotion here: her exhaustion in her father’s company, her frustration in Sensei’s classes and it all comes to a head when at her breaking point, completely devoid of art, finally, finally picks up the pencil and starts to draw again. Ironic, but very human. She’s still got a long way to go, but it’s a start. And trust me, Akiko has not changed much. She’s still childish, selfish, insensitive. In her excitement, she repeats the same old mistakes. She forgets Sensei. Looking back at the age of 35, with hindsight and new maturity, she realises just how much she owes him. Just how much she’s always owed him. How he, without knowing, gave her so much strength and so much discipline, that later on, when life hits Higashimura again, she can still pick up that pencil and draw.

The love of drawing is embodied in Sensei. He’s hyperactive, annoyingly dedicated, with a simplistic view of the world. But he loves art. It’s his cure-all for every ailment. Feeling sick? Draw. Feeling mad? Draw. Feeling sad? Draw. Draw. Draw. His attitude can be double-edged sword (especially for the perpetually lazy and demotivated Akiko), but his earnestness is disarming. His love for art and his identity are so intertwined that, as the manga came to its heartrending finale, I could no longer tell the two apart. To whom had Higashimura dedicated this manga? Her sensei? Or to drawing? Where did one start and the other end? And proof of this man’s love for drawing lives on in Higashimura herself, who draws with alarming speed and accuracy and has crunched out a vast number of series in her lucrative 20 year career. I’m sure he’s proud.

I stand on the edge of a precipice. Soon I will be thrown off the edge into the uncertainty of adulthood. For now, I’m clinging on, trying to enjoy the rest of my teenage-hood and not think of all the years I’ve wasted. I think about art a lot. I’m not like Akiko- our backgrounds are different, our cultures are different, our parents are different. I’m slowly edging into medicine, not because I like it, but because it’s what’s sensible and I never want to be unemployed. But I still dream of silly things, like becoming an animator or a screenwriter or even a director. I want to work in film and television. I want to revolutionise animation. I want people to say my name with awe. I want pretentious interviews and tons of Oscars. But…how? What time do I have? These next two years are going to be crucial for me as I work hard to get respectable grades, but also for art. Where will it fit into all this? Medicine isn’t my passion, but what if–what if it becomes my passion? What if, in 10 years’ time, I look at the me now and think, ‘Wow, so unrealistic, such an idiot’? I don’t want that to happen. Or what if, 10 years from now, I’m still craving art? I’m still becoming a doctor, headed firmly down that route, yet my dreams of success are smeared with paint and charcoal, hunched over an animator’s desk, bringing a character to life? Which is worse? Which is better?

Higashimura concludes that “all people who draw were born to do that”. Is that really true? I don’t know. But for now, for the me in this moment, I have to pick up that pencil. It’s all I can do. Just draw. Draw. Draw.